A lifetime can pass between breaths when you’re dreaming in the middle.

Josh Garrick watched a determined Greek art curator striding across a palatial Athens apartment, transfixed by a curious sheet of aluminum laid absentmindedly on the far side of the room.

“Who did that?” she asked.

“I did,” he said, not an inkling of the secret crusade those words would launch.

Four months later, a three-way blur of loud Greek suddenly went silent. Then the national museum director, sitting at the commanding end of an imposing desk, made the offer that set Garrick’s jaw agape. He remembers having to tell himself to breathe again, as that same ambitious curator stared at him wide-eyed, emphatically nodding, planting the answer that should have already broken that too-long silence: “Yes.”

Inhale.

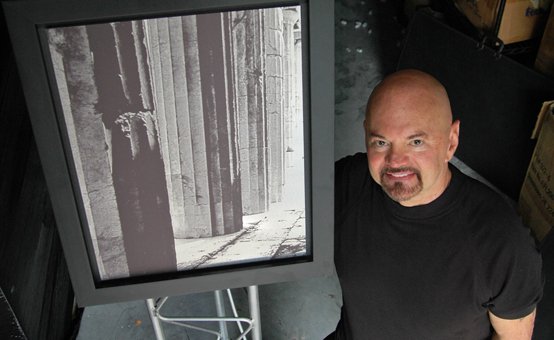

After a lifetime worshipping ancient Greece and capturing its art from bizarre angles that would define his artistic career, the wait was over. The dream Garrick never dreamed was coming true — the exhibition of a lifetime.

The offer that left him speechless isn’t just any. He’d been to the museum before; he’d taught and led tours there. So he knew that in its 124-year history the National Archaeological Museum of Greece in Athens hasn’t tended to exhibit American artists, let alone from Garrick’s launchpad of the brand new Jai Gallery in Orlando. That’s when they told him they never had. The Greek-obsessed fine-art photographer would be the first.

Friend and exhibit curator Iris Kritikou was the one who stood enrapt at Garrick’s aluminum photograph in September of last year, and then secretly set up the surprise meeting that would make his dreams come true.

“Josh is somebody who loves this country because of both its past and its present, and I hope its future,” she said. “[Greece needs] this kind of support, especially these days.”

When the museum’s massive doors open on his exhibit on Sept. 12 this year, they’ll reveal another rarity: the artist who created it is still alive. When Garrick arrives he’ll blow the average artist age curve by more than 100 generations. That’s apropos for Garrick; he started his obsession young.

Dreaming in black and white

Garrick doesn’t know why, but when he was 12 years old he built a Greek temple. His skin slicked with bleach-white plaster of Paris, he molded the contours between his small fingers until it was just right.

The poor boy growing up in a farm town hadn’t seen anything like it before. Not many of the residents living among the patchwork of green that stitches together rural Pennsylvania had; not in person anyway. But he could hold it in his hands, a dream in black and white.

“Seeking the ancient Kallos” will be shown at the National Archaeological Museum of Greece from Sept. 12, 2013 to Jan. 8, 2014.

For a boy who could never imagine seeing the real thing, that was as close as he would come to the land of the ancient gods for 11 more years. An eternity in a child’s dreaming eyes passed in a blink on the other side of the world.

It would be a long journey to Athens. But Athens had waited far longer for him.

Coming home

More than 2,000 years beyond the apogee of the age of the gods and a republic in novel nascence, beyond conquest and ruin, the Parthenon’s western face lit up in the amber afternoon light. And a 23-year-old Garrick was finally there to see it, as tears filled his eyes.

“I have always, always had this fascination with ancient Greece,” he said. “It’s inside me. Other than that I don’t know, but it’s there. And I love the fact that it’s there, and I love the fact that it’s been there all my life.”

Far from his farm town’s rolling fields, Garrick said he stood at the cradle of the idea that a boy could go as far in life as he dared.

“Here, a person born in poverty can move on to greatness,” Garrick said.

Given the chance to document his obsession, he dove in. It’s difficult for him to name a Greek monument or artwork he hasn’t seen, photographing the decay and restoration of millennia of iconic sculpture and architecture in unusual new ways.

“He gives it a contemporary view,” Kritikou said. “This kind of art is perpetual. I think the way he photographs it, he makes that visible.”

Stop by a museum that he’s in, and chances are you’ll find him laying on the floor, camera in hand, capturing a tribute to antiquity.

“I feel this incredible responsibility to the genius artists of over 2,000 years ago who created these things,” he said. “I’m bringing hopefully a greater appreciation to what’s there.”

Decades since his first trip, he can’t count how many times he’s been back to photograph those ancient glories that time has slowly taken away. Every time he goes, every trek he takes up that hill to see the Acropolis spilling across the landscape in front of him, every time he gazes at the Parthenon bathed in sunlight, it’s a homecoming, he said.

But those long days in the sun also nearly killed him, as he developed a skin cancer that almost went undetected. But he persevered, continuing to photograph ancient Greece at his trademark odd angles, continuing to teach art even as cancer struck again. Again, he survived.

Help local talent make art history! A fundraiser to benefit Josh Garrick’s exhibition in Greece will be held from 6-9 p.m. June 27 at Jai Gallery in Orlando. Please RSVP to 407-522-3906 to attend.

They say pet owners eventually start resembling their pets. Garrick, the lover of ancient figures etched in stone, slowly became a chip off the old block. Blessed with better skin than average, his face has aged enviably, but chemotherapy stole his hair years ago. A chunk of his left foot is missing from surgery. The sun playing across his arms just right reveals the ghosts of skin cancer biopsies, telltales of the whips and scorns of time.

The Parthenon’s long overdue reconstruction project, which Garrick has documented for more than 25 years, has taken 30 so far. Garrick’s hoping he’s done with his own reconstruction in a bit more than three. After all, he has to look his best for opening night, when the gallery lights illuminate a life spent capturing eternity in the blink of an eye.

[pi_wiloke_infobox title=”” content=”Help local talent make art history! A fundraiser to benefit Josh Garrick’s exhibition in Greece will be held from 6-9 p.m. June 27 at Jai Gallery in Orlando. Please RSVP to 407-522-3906 to attend.”]

The big night

He’s envisioned that moment a little; even if it’s a night he never dared dream of before. When the doors open and the crowd pours in, he knows where he wants to be standing.

He calls it “The Little Jockey,” his photograph of a sculpture pulled from the bottom of an inlet to the Aegean Sea after 2,000 years. The bronze boy and his horse were battered by the churning water, needing years of reconstruction before they were reunited again, still not quite complete. The life-sized horse looks enormous underneath the boy, who couldn’t be more than 12 years old.

Something wrought in that weathered bronze called out to him. Garrick studied it, searching. Then he saw it.

“It’s always been a thing of mine to take the photograph that’s not the obvious one,” he said.

He lay down on the ground, aimed his lens high, and pressed the shutter.

The black-and-white photograph barely captures the boy’s shadowed face, or the horse’s as it races ahead, scarred with fissures, mid-stride on an impossibly long journey. The light cascading through the shadows draws your eyes along the pits and holes on the boy’s arms, silenced harbingers suspended in time.

But some of the sculpture couldn’t be saved. Most of the reins were consigned to fate beneath that ever-churning current. Just a small piece remains, still held tightly in the boy’s tiny hand, willing the horse onward to a horizon only they can see.