At the conclusion of Catherine Lampert’s essay in the catalog that accompanied the 1993-94 exhibition of Lucian Freud’s work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the art historian wrote how Freud expressed his absolute faith in the work of the Spanish painter Diego Velázquez.

HERE ARE OTHER SIGNIFICANT BOOKS ON LUCIAN FREUD:

■ Man with a Blue Scarf: On Sitting for a Portrait by Lucian Freud (published by Thames & Hudson), by Marin Gayford

■ Lucian Freud Paintings (published by Thames & Hudson), by Robert Hughes

■ Lucian Freud: Recent Work (published by Rizzoli), by Catherine Lampert

■ Lucian Freud (published by Random House), edited by Bruce Bernard and Derek Birdsall

The last lines quote Freud as saying, “I believe in Velázquez, more completely than any other artist whose work is alive for me.” She goes on to say that Freud quotes what the Spanish writer José Ortega y Gasset had said about seeing Velázquez’s masterpiece Las Meninas: “This isn’t art, it’s life perpetuated.”

In a way, when a great artist such as Lucian Freud dies (he died in 2011), writers themselves seem hell bent on engaging in acts of perpetuation: Namely, they publish memoirs that take a stab at summing up the artist’s life, in an effort to keep him or her alive in our memories. At best, these works tend to chisel away the incidental or insignificant aspects of an artist’s life, only leaving the essence of what made the artist tick and tacking that up for all to see. At their worst, you sense the author has an ax to grind, eventually wielding it to massacre the dead painter’s achievements in a very public manner.

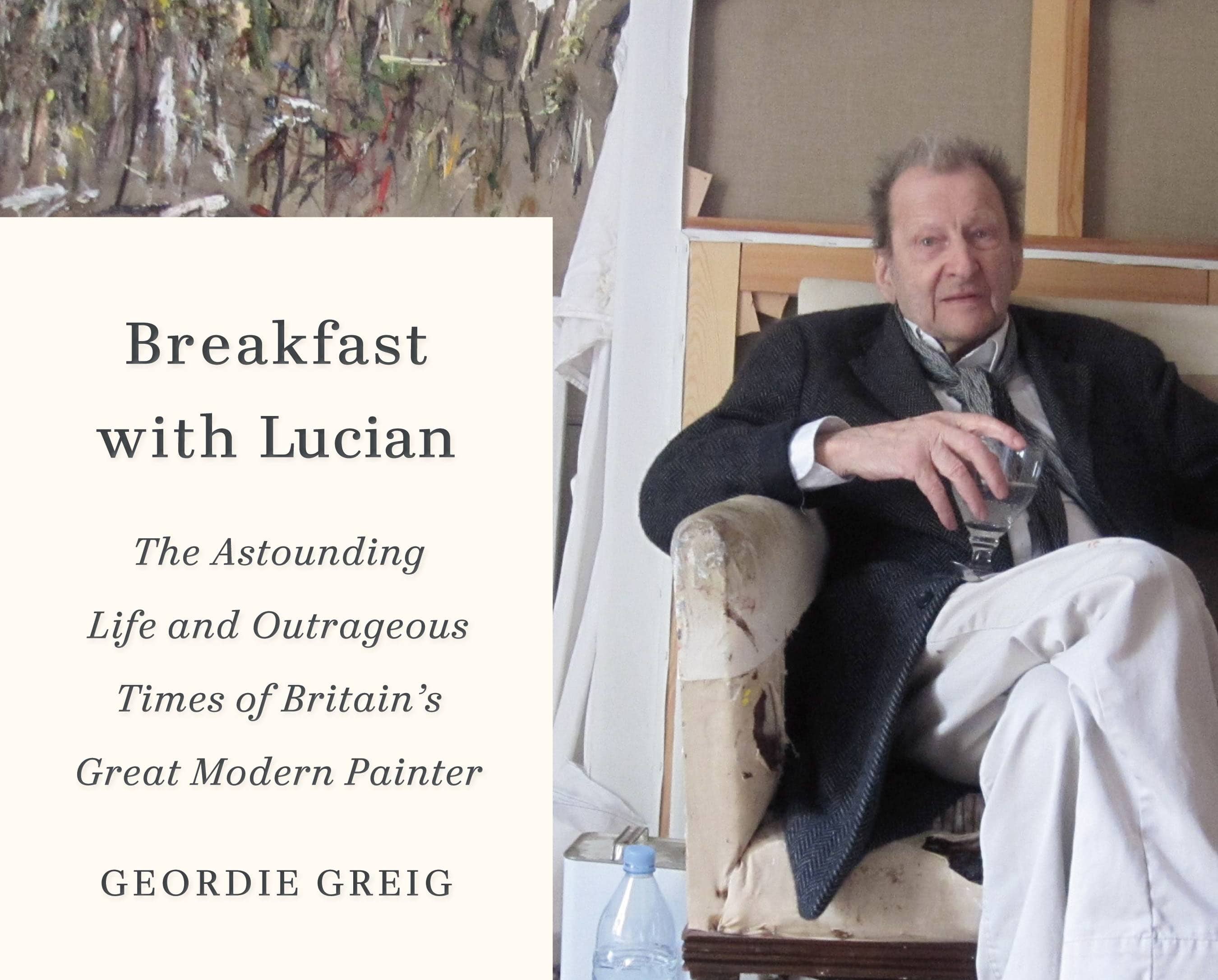

Last year, British journalist and editor for The Mail on Sunday, Geordie Greig, authored Breakfast with Lucian: The Astounding Life and Outrageous Times of Britain’s Great Modern Painter (published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux). For the most part, the writer does a decent job at capturing what made the great British realist and portraitist so captivating.

Additionally, Greig included some striking photos in the book. Overall, the book is enjoyable to read and presents some wonderful details about the artist. But Greig does tend to get too involved in the gossipy or shallow elements of his life. For example, the writer describes Freud’s love of fistfights.

Near the beginning of the book, he also includes Freud’s only iPad sketch, which in this case was of a horse, although it looks like a giraffe. These elements are simply not insightful to Freud’s character or importance.

Greig also takes 15 pages to get to what should have been the first line of the book: “Irrespective of all these contradictions, what ultimately made Freud remarkable, of course, were the paintings.”

But Greig does pinpoint Freud’s achievements: “In the 1950s and ’60s, when abstraction and postmodernism were in the ascendant, he continued obsessively painting the human figure in a studio.” For many figurative artists, Freud was the artist who kept the flame of figurative art alive in painting, until the late 1970s, when it came back into vogue.

My main problem is that although the book goes into various aspects of his long life — his life as the grandson of Sigmund Freud, his family, wives, friends, lovers and others — some of the narrative at times borders on soap opera. It’s absorbing to a point, but Greig just adds too much detail. But I’ll give him this: Because Freud was often silent about the meanings behind his paintings, and because his subjects and their identities seem complexly weaved into the content of the works, it is interesting to read about who his subjects were and how they are connected with him.

Not surprisingly, Chapter 8 (“Paint”) is my favorite. In this chapter, Greig recites to Freud, over breakfast, various things that the great artist had said decades earlier in a magazine interview: “My object in painting pictures is to try and move the senses by giving an intensification of reality. Whether this can be achieved depends on how intensely the painter understands and feels for the person or object of his choice.” To Greig’s surprise, Freud felt that his views had more or less barely altered and that those statements still summed up how he felt almost a half century later.