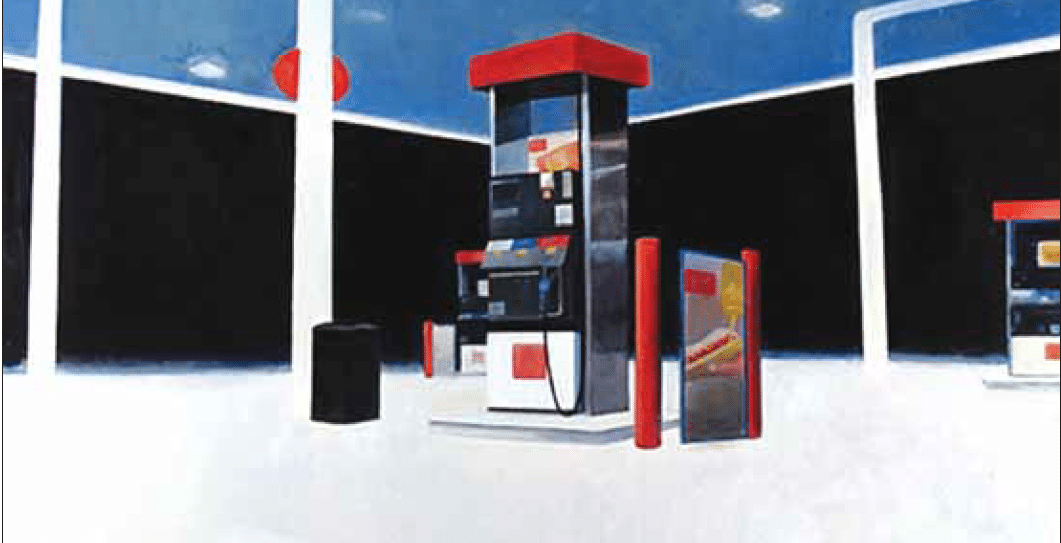

Best known for his large-scale oil paintings of “non-places” (airports, gas stations, highways and train yards), Washington DC artist Trevor Young has witnessed his artwork explode on the national art scene throughout the last few years. The 34-year-old has already exhibited in such prestigious institutions as The Orlando Museum of Art, The Corcoran Gallery of Art and the Baltimore Museum of Art.

“Mark Augé coined the term ‘non-place,’” Young explains. “Essentially, [he] has a negative look of non-places. He has a very harsh look at shifting culture and how it’s making the world colder and generic. [But] I actually love it. It makes the world smaller and creates the global village, which allows people to move freely, go anywhere in the world and not even speak the language, but just function at a great ease. So my work became a response to Mark Augé and his lamenting the shift in culture. I felt he wasn’t getting non-places, how great they are, the power of them.”

Currently represented by Civilian Art Projects in Washington DC, Young has also exhibited his signature works at Aqua Art Miami, Sloan Fine Art in New York and Billy Shire Gallery in Los Angeles, and in a solo booth at SCOPE during Art Basel Miami Beach 2010. The opportunities have provided Young with the resources and support necessary to pursue his art full time, but Young is quick to point out that he was only able to gain this level of career momentum through clear goals and strategic planning, including cultivating a strong base of collectors and supporters.

“To be a full-time artist, you have to balance business with art. You have to have a dedicated studio practice. Work ethic is number one. Painting always comes first. I put close to 60 hours a week into studio painting. Even if I have other projects or commitments, I spend at least 40 to 60 hours in the studio because I derive so much pleasure from painting. Some people watch television; I don’t. I go into the studio and paint; that’s my escape.

“I am [also] enthusiastic about people and really love other artists and people who care about painting. I am naturally able to find those people …There are so many great artists out there who cannot support themselves. They may be a better painter, but not as enthusiastic about people. I like my relationships with my [collector] base and the people who support me and take care of me as an artist. It’s authentic and meaningful.”

Building a Foundation

Like many artists, Young knew at an early age that he wanted to become an artist. Growing up in the DC area, he had the pleasure of looking at great paintings at the National Gallery of Art, where, as he explains, “Matisse, Whistler and Diebenkorn became my mentors.” He eventually pursued painting at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia, and at age 19 worked at a local art store, where he was asked to become a demo artist for Winsor & Newton. This meant free paint and endless supplies. “I was addicted. This opportunity to have supplies and free time, because my job was to make art, early on, really procured the vision that all I ever want to do with the rest of my life is enjoy painting and become a full-time artist.”

Right out of college, he began to apply to shows in and around DC and Philadelphia, as well as in spaces up and down the East Coast. He started to build a collector base immediately and consistently followed up by sending letters inviting the collectors to see new work.

“You have to like people. I love people. I love artists. And I love people who love the arts, so naturally, I am enthusiastic about them. I’m quizzical and like to follow up with them. The pleasure of networking is important. I hate that term, because for me networking is having a good time. [Being a full-time artist] has a lot to do with people, being social and enjoying others. It’s the ability of the artist making a commitment to the collector as much as the collector making the commitment to the artist. It’s a very unique relationship. If a person is willing to go to a gallery space to see your work, they’re interested. They’re not there to drink coffee.

They’re there to see your work. Those are the people who need to be respected and nurtured because they will support an artist.”

Young has used some unorthodox promotional techniques to get the attention of these core supporters, including once giving a high-end dealer a painting in trade for her to come see his work early on in his career. This moment proved to be a major turning point for Young because the dealer was so impressed with the work that she gave him a solo show, which subsequently sold out. With more money to pour back into buying supplies, Young was finally able to transition from working part-time and making work at night to being in the studio full time, and he wasn’t about to let the chance pass him by. “That was the opportunity I needed and had visualized as a younger man. I only wanted to be in the studio for the rest of my life. Every single time I think painting’s boring, I find a new problem, a new challenge. This was my goal, to create challenges for myself. I never looked at it as a commercial venture either.”

A Strong Commitment to the Work

In addition to developing relationships with collectors on his own, Young says that getting gallery representation at Civilian Art Projects has helped him secure his commitment to pursuing his art full time. In order to build a strong reputation as a serious artist, Young believes in closely controlling where one exhibits his or her artwork. For him, that means exhibiting only in spaces that are 100 percent dedicated to art. Not only was Civilian Art Projects such a space, but gallery founder and director Jayme McLellan was already catering to the precise crowd Young enjoyed socializing with.

“I knew Jayme and wanted to show with her because this was the gallery all of the artists and musicians went to, attended openings and hung out. And she hung out with them. Those are the people I like. This is where I get my energy, from other artists … Then, a very unique opportunity came along. A collector from Los Angeles wanted to buy my work. [But] because I wanted representation with [Jayme], I asked for her to broker the deal. It was a big risk for me, but a few weeks later she invited me to participate in a group show at Scope 2009 during Art Basel Miami Beach. We had success during Art Basel Miami Beach. It’s been a year now. It’s become a synergistic friendship. I have a lot of respect for her gallery. It’s a very healthy environment. The artists are very impressive, so naturally I feed off of the energy of the other artists. I’m producing the best work I’ve ever produced because she trusts me so much to take risks.”

Hard work and good times seems to be paying off for Young, who will be showing new work this spring in a solo exhibition at Civilian Art Projects. Backed by a strong work ethic, determination and a supportive family, he has been able to pursue his dream of doing what he loves as his full-time career. The best advice he can give to other artists looking to build up similar career momentum is “Make strong work, and get the work out of your studio.” For Young, creating art to be seen and enjoyed by others is the meaning of his career and meeting this goal is his passion: “This is the most pleasurable way to live, and I had to figure out a way to do it. It also becomes your identity; it gives you strength.”

E. Brady Robinson is Associate Professor in the School of Visual Arts and Design at University of Central Florida, Orlando. She received her B.F.A. in Photography from The Maryland Institute, College of Art and her M.F.A. in photography from Cranbrook Academy of Art. Visit her Web site at www.ebradyrobinson.com.

© Professional Artist March 2011