As a veteran of seven artist residencies, I can testify that they inspire creativity and build careers. They also require self-discipline and clarity of purpose. When you apply for a residency and live at the venue, you need to clarify both what you hope to accomplish and what is expected in return. Clarity, self-knowledge and good communication will contribute to your success.

Your Presence is an Asset

First things first, your presence in a residency program is an asset to that institution. In each of the programs that I have participated in, the hosts have provided me with services such as lodging, free passes, and in one case, a cash stipend. I cannot speak to paid programs — they are obviously a completely different experience. Regardless, remember that as a professional artist your presence provides a unique service that your host desires, whether you teach, donate artwork or create fresh visions. In short, your time and presence are valuable.

Create Opportunities Yourself

My first residency was in the rugged woodlands of upstate New York, hosted by a nonprofit foundation. I engineered the residency, proposing it to the organization’s director. My lodging consisted of two tents, which I provided, while the foundation provided a tent platform, and access to kitchen and bathroom facilities. Crucially, they formalized our relationship with a letter from the foundation making an official invitation. This was important because it turned a casual interaction into a formal sponsorship, one that could be used on my resume and as a reference in future applications. In addition, at the end of three months, they provided me with an exhibition space and opening that coincided with their largest annual event.

This residency gave me unlimited and immediate access to the scenes I wanted to paint. Distances to sites I admired were measured in feet, and the time available to paint was limited only by dusk. It turned out to be a terrifically productive summer for me, during which I produced strong, consistent art. The residency also gave me my first credentials and a record of success in this type of program. I also received a letter of thanks and recommendation (something that I strongly suggest obtaining) which served me in applying to other programs.

There were limitations. The location didn’t have any history of art residences, which meant that I had to design and create anything I wanted. As an undercapitalized organization, there were also no funds available, and I was occasionally drafted as free labor. Despite these minor complications, I was able to create a high-quality body of work and establish credentials for future residencies.

The Next Step: National Park Service Residencies

Afterward, I began steadily applying for National Park Service Residencies, since their missions of preservation and education felt very close to my own aesthetic. My breakthough came when I was tipped off about an artist-in-residency (AIR) program at a lesser known NPS unit in Wilton, Connecticut — Weir Farm National Historic Site. This 60-acre farm was home to J.A. Weir, an impressionist painter, and the park maintains a commitment to keep living artists working on site at all times.

This was my first professional experience with NPS, but their residency program is still one of the finest I have experienced. I cannot overstate the positive impression the NPS staff made on me. Historians, archeologists and biologists have restored the site, both buildings and grounds, to its 19th century appearance. The Natural History Association maintains a house and generous studio for the AIR and pays the artist a stipend. I had an amazingly productive two weeks painting outdoors at the peak of a New England autumn. I did not have to teach or donate work; the only thing required was that I make art. This excellent residency’s only limitation was that the housing and studio were a half mile off site.

Find Inspiration and Solitude — But Not Too Much!

In the summer of 2001, I was thrilled to be invited to do a residency in my first western park — Glacier National Park in Montana on the continental divide in the Rockies. The residency provided a beautiful cabin on Lake McDonald. My gracious hosts had filled the cabin with art books, especially those about the Western painter Charlie Russell, who was active in the area and something of exemplar for the park. The location was inspiring and comfortable. I was so appreciative that I set up some open houses for park visitors at my cabin. The residency was very exciting, but in retrospect less productive than others because the areas that inspired me were more than 10 miles and 3,000 vertical feet from my lodging, up the precipitous Going to the Sun Highway. Luck of the draw, I guess. Remember, location of your subject matter is a major consideration with AIRs.

Prepare to Be Adventurous

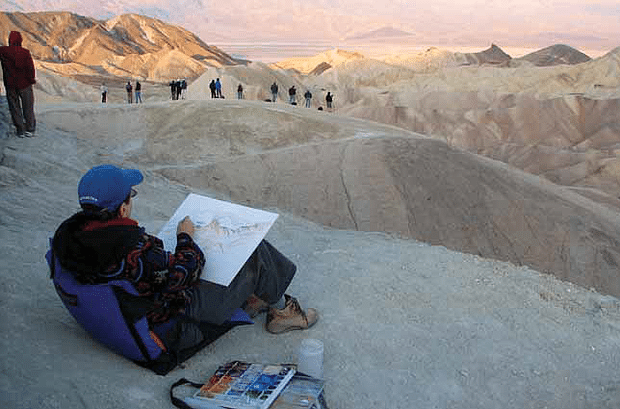

In recent years, I have served in National Parks of the California Desert. It was very important to have a background in other parks residencies, as well as desert hiking and camping, before undertaking these programs. Living and working safely in these harsh regions requires special care and preparation. I completed a residency in the western Mohave, where I was given a small house for an entire month in an incredibly scenic valley surrounded by sculpted granite hills. Now, to be sure, this house was “off the grid” — up a dirt road, without electricity and about 50 miles from the nearest town. For me, location was everything, though, and placement amidst beauty without distraction was a formula for success. Early on, I learned the rhythms of the desert, painting early and late, resting midday, locating areas of shade or carrying my own and always having lots of water. Within these parameters, I created an abundance of work.

Embrace the Challenges

That visit to California led several years later to an invitation to an artist residency in Death Valley National Park (DVNP), the largest National Park outside Alaska. My wife, artist Janet Morgan, was able to join me. In a way, Death Valley consists of two parks — the easily accessible areas near paved roads around the visitor’s center at Furnace Creek, and thousands of miles of wilderness valleys, mountains and canyons accessible only by dirt tracks. Huge and challenging, Death Valley provided us with fewer resources and asked more than other AIRs; yet, in many ways it was our favorite program, a location which we returned to on four occasions. The NPS didn’t offer lodging, but they gave us a tent, a VIP campsite and a Park pass. The scenery is vast and impressive; exploration is unending, and the élan of the NPS staff inspirational. We were hooked.

“It turned out to be a terrifically productive summer for me, during which I produced strong, consistent art. The residency also gave me my first credentials and a record of success in this type of program.” ~ Gregory Frux

Our time in Death Valley developed a pattern — traveling outward, painting and drawing in the wilderness, then returning to the vicinity of the visitor’s center to work with the public. Here, the NPS interpretive staff were true collaborators, helping advise us on destinations and imparting an education that deepened our experience. As a result, we were inspired to work more closely with NPS. We gave talks about our work, taking visitors on virtual tour via our paintings. We also led watercolor classes in nearby Golden Canyon, taught art to local students and donated work to the Park’s museum.

Although the residency at DVNP is no longer active, the results of this fertile collaboration continue to grow to this day. They include more than 100 works of art created by me and Janet, several lecture engagements, a set of art cards and a book project.

Make Residencies Part of Your Career

Artist residencies have become an important part of my creative output. I attribute my success with them to careful selection and paying attention to locations, both for access and visual interest. Requirements by sponsors have been fair and easy to fulfill. In fact, my hosts have generally inspired me to contribute more than initially asked, and that contribution has become part of my creative output. I’ve continued to keep a critical view of what I want and hope to accomplish in each experience. Every time I consider a program, I decide if I can commit to delivering what the program needs. I encourage you to explore residency opportunities and discover how they can create a synergy that will move your career forward.

To celebrate Professional Artist’s 30th anniversary, we are gifting our readers with 30 complimentary articles from our archive. This is a complimentary copy of an article from the April 2011 issue. Click here to subscribe to Professional Artist, the foremost business magazine for visual artists, for as low as $32 a year.

Gregory W. Frux and his wife, artist Janet Morgan, live in Brooklyn, New York, when they are not working in remote locations such as Morocco, Patagonia, Antarctica and Death Valley. Visit Gregory’s website at frux.net and artandadventures.com.